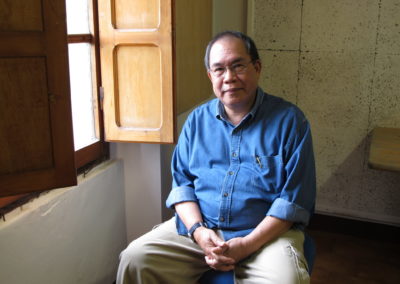

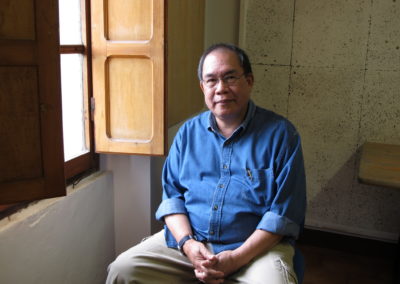

Jose Dalisay

I came to Civitella to begin work on my third novel, and was glad to be able to do that, with surprisingly more ease and at a faster pace than I had thought possible. Along the way, and as a break from the novel, I was also able to complete work on two other books—one of poetry, the other nonfiction—which weren’t even in the plan. Civitella is full of happy distractions, and I certainly needed them; but with judgment and focus, wonderful beginnings and closures can be made.

Excerpt, from my novel in progress:

The stand was no more than a shack on an empty lot which the dealer and his family had taken over for their thriving business; one wall of the shack was a faded Pepsi-Cola sign sporting the old swirl bottlecap, the size of which suggested a huge billboard that had likely crashed during a typhoon and had been dragged over to the lot to serve a more immediate purpose. A girl of about three peered out of a window in the shack, her eyes bright as marbles, a pink finger in her mouth; some movement behind her suggested other occupants, very likely her mother and at least one more child. Whoever was in there was cooking in the back, from where smoke curled up over the shack and its roof, which had been battened down by old tires. The smoke was greasy, and tiny black flakes of soot flew in lazy circles in the air. Joel began to understand what the strange smells that had surged into the car when he pulled the window down were: burning hair, drying blood, and a hint of ginger, or was it lemongrass?

The Land Cruiser sped off and Rodney and Chinito took their places before the dealer—a big man with a Buddha’s belly draped by a Chicago Bulls 23 shirt, denim shorts, and double-vision eyeglasses with thick black frames, a cigarette in one hand and a cleaver in the other. Joel stayed in the car, but looking out he saw the dealer’s wife tending to a cauldron of meat, her brow wet and shiny with the steam rising from her cooking. The little girl in the window now appeared at her side, gnawing at what might have been a rib left over from their midday meal. At the back of the lot, a boy of about ten was stacking firewood into a pile, wood that had been salvaged from the floors and posts of demolished houses.

Near that wood pile stood a gathering of goats—at least eight of them, of various ages and sizes, in colors that ranged from glossy black to a delicate brown approaching mustard-all tethered, several to a side so that they faced each other, to an iron railing that their owner had fashioned out of the headrest of an old bed and had stuck deep into the ground. The space between them was littered with dry grass on which two or three goats munched listlessly; behind the goats the earth was dark with their stool, which shone like black pearls.

Except for a slender kid that clung to its mother’s haunch, it was impossible to tell if the goats were of one family, if they had been raised together on that lot, or if they had been delivered there from other farms and backlots in Bulacan or Cavite, to be killed and sold on retail in the heart of the city. Joel had failed to notice them immediately because they had been keeping quietly to themselves. They were wide-eyed and skittish, their neck muscles throbbing, but they were not bleating wildly, as though silence and stillness would render them invisible. The bones and entrails of goats that had fed at the same trough that morning attracted flies in green pails just a few feet away, beside plastic jerrycans of water trucked in from elsewhere. Behind the smoke and the steam of her cooking, the dealer’s wife flayed a leg expertly on a small table, tossing strips of flesh into the catchment of a weighing scale suspended from a post of the shack itself.

“Just two kilos, manong,” Rodney was telling the dealer. “We can’t finish a whole goat, there’s only three of us to eat everything.”

“It’s his birthday,” Chinito added. “Give him a good price for his birthday.”