Matthew Thomas

I’m a night owl. Western culture doesn’t consider the nocturnal laborer’s efforts especially virtuous. Benjamin Franklin summed the prevailing sentiment toward those who rise late (however noble the struggle with art may have been the night before): “Up, sluggard, and waste not life; in the grave will be sleeping enough.” Whether one wants to blame it on the Protestant work ethic, or an agrarian culture that learned to prize sunlight, or simply the pious notion that nothing good happens at night, those who rise early to work feel warmly welcomed into the family of man. Those who stay up late, on the other hand, must skulk around feeling vampyric and diabolical. My natural rhythm is nocturnal; jet lag encouraged that at Civitella. I rose some days shortly before lunch and stayed up some nights until four or five in the morning. Seeing the happily pausing Fellows and staff at lunch sparked in me a brushfire of shame at the thought that they’d been dutifully working all morning. This shame carried usefully over into the evening; when others were tucking into bed, a job well done, I was tucking into the work that would allow me to feel I’d earned my place at the big table. It was only past two in the morning that I usually felt I’d won the right to sleep. I admit all this with more than a little chagrin—and yet there is the secret pleasure of staying up late: the stolen time, the feeling of having the planet to oneself, or, if not to oneself, to oneself and that silent, farflung band of exiles who take light steps and monitor every creak in the floorboards, who hear the sound of chests rising and falling as a metronome that we hope will never be arrested, lest we lose our solitude. The obvious question—why not rise early and live the same experience at the other end of the day?—has an equally obvious answer, and that is that there is something pleasantly perverse in the refusal to knuckle under to circadian rhythms and received notions of what the right apportionment of our hours is; this is especially true in light of the increasing awareness of how deleterious a lack of sleep is to the body. There is something willful in such voluptuous self-neglect.

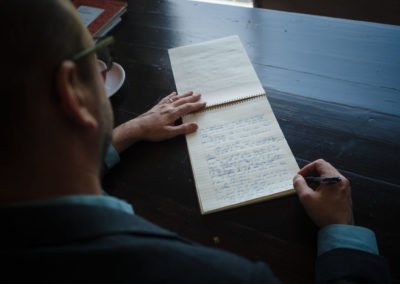

This constant brinksmanship was the backdrop to my efforts at Civitella. And yet no place has given me more energy, or inspired me more, or helped me get more work done in a short time. How calming it was to step out of my ivy-framed double doors at Upupa and listen to the rhythms of the castle at night, with its lone light on in some sleep-abandoned hall! How blessedly secure did I feel behind the outer walls when I took a short midnight stroll on the lawn, the cacophony and responsibility of ordinary life kept securely at bay. How blessed was the table at which I sat to write, and how helpfully unadorned the room in which I did. Gone were the stacks of books unread in my office at home; in its place was a much shorter stack of equally unread books. Gone were the hundreds of pieces of my children’s art with which I plastered the walls; instead, I had one precious piece from each, made in the run-up to my departure, with the very castle I was now looking at the focal point of their imaginings. I had stripped life down to the barest essentials. I hadn’t even learned the code for getting into the gate until about a week in, because I’d made an antlike circuit from my door to the dining room and back. The weekly excursions were my outlet to the world, along with the trips to the market, where I got, along with breakfast foods, chocolate, cookies, and the water for my tea that my fellow fellows rightly roasted me for. The rest of life was table, chair, teapot, and bed—and the extraordinary company of my compatriots in the various arts, and the delicious meals, and the sense that it was not only appropriate to spend the bulk of one’s waking time—Luciferian in its lateness as that time may have been—attempting to make art, but that it would be inappropriate not to, when so many people on the staff had gone to such great lengths to make it possible for one to do so. And so I wrote, by hand, on my notebooks, and when I was done I closed the notebook and went right to sleep, whatever hour it was. And when I woke I went right back to the table and started all over again. And in-between we ate, and laughed, and regaled each other with stories, and played spirited games of foosball and ping pong, and generally fell in love with each other in the aggregate. I’ve never felt so quickly at home in any group, never felt so generally embraced, nor so specifically. We were eager to see each other at meals, and to walk with each other down the streets of beautiful Etruscan cities, and when we parted to head to our studios, we did so with the lighthearted gravity of people who knew what we were in for when we sat down at the desk, or stood before the corkboard with a canvas pinned to it, or sat at the piano, and who also knew how privileged we were to get to do so. I loved my time in Civitella more than I could say; I’m sure every Fellow feels the same. It allowed me to re-inhabit my book, but what’s more it allowed me to re-inhabit my life fully, and it hasn’t felt the same for me since I left. I’m sure that’s common, too. How could it not be? There’s no place like Civitella. Civitella will inhabit a cherished perch in my heart as long as I live. There will always be a part of me that never left it.