(1964-2005)

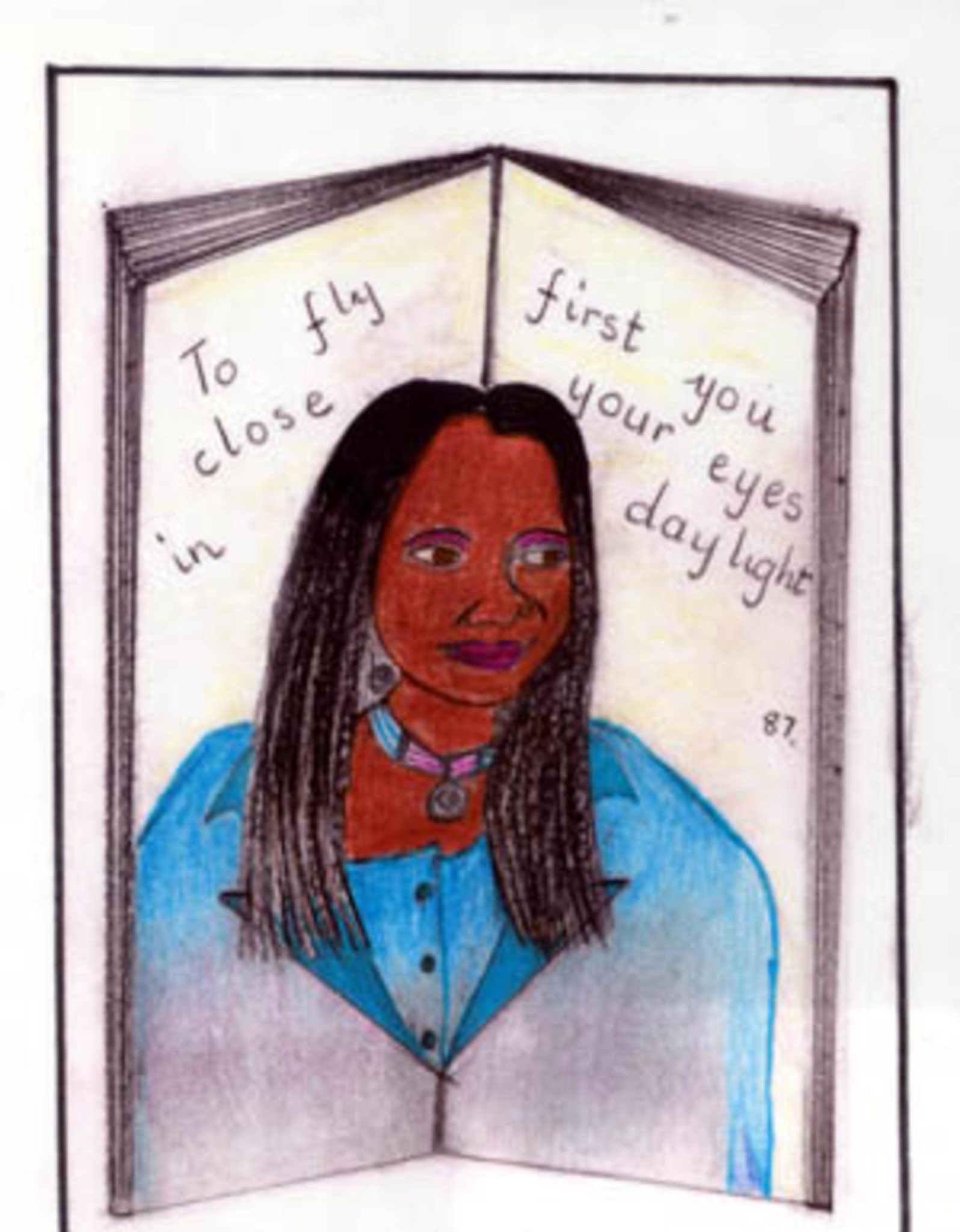

Confusing the Dead

Synopsis: This chapter from the novel “Confusing the Dead” takes place during the construction of the Kariha Dam, in what was then Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. This dam, though vital to the development of the country caused great displacement and thousands of deaths.

The water explodes, personal histories are let loose. Bodies swell to the root of trees, uprooted. Dry logs emerge, float freely, confusing the dead. At night dark skin glistens and reflects the stars. Arms glitter. The faces are thick with mud. Bodies choke with cement, wrapped stiff, wedge along the trees that have resisted the force of the explosion and now continue upright beyond the reach of the water, waiting for the bodies. In the water is a reflection of stars, which dies with the morning leaving a mirror of trees. Outlined, the dreams of white men who want to harness water, not bodies now floating, black, reflecting the day sky. The night sky is gone, so too the continent of skin. Dark. Sliding away, the way light slides on water. Nobody would touch the bodies cleansed of living, except fishermen used to pulling nets from the water, to bringing out the dead. Now they cast their arms out and bring in the harvest, which leaves their minds billowing larger than their own nets, larger than their combined histories. Slow arms move under the water, pull blindly at reluctant stars sparkling over each thread of net. A drop of water is like a source of light; life ends as abruptly, as quietly. A silver moon breaks on the moving arms of the living, on the skin of the dead.

In a community like Zimbabwe in which women suffer great losses each day, there is no doubt that the pressures of such a community impinge on the aims of a female writer such as I am. I am concerned about Zimbabwean women. When I see the furrowed brow of an African woman and the pain on her back my heart beats terribly; I close my eyes even in the middle of crossing a street. I know that the moments in this woman’s life are unspeakable. I wish to restore some tenderness into the word. Then I write in search of this tenderness. I hate all sorts of betrayals between men and women. I returned to Zimbabwe in order to be closer to my subject matter and to reduce the brain drain in the continent. Every society is not static. I could not write about Zimbabwean woman while living abroad. However, this nearness to the world of Zimbabwean women who are my main subject forced me to focus on style, structure and language as major challenges of my creativity. It is not enough to write about women. I have to transcend that subject and make my reader feel that this book has been necessary in another way, that the novel has expanded a world, broadened a vision for individuals – of places, of emotions, of possibilities, beyond that of women. I want my reader to return to the novel with a new desire for their own personhood. I search for dignity in humankind. I seek celebration. A great love of life. I laugh. I laugh even after I have written the harshest of narratives. It is necessary. When I laugh it is difficult to imagine that I wrote about that heroine who had that brutal abortion. When we meet then you know this is not my abortion. When you read it, this abortion is mine. When I write it; the abortion is in my bones somehow and that thorn which causes it is vibrating between my fingers, causing a deep harm to my body. This moment must pass and I must survive it, after all, it has come from my imagination to my fingers – like blood flowing.